Wind Power in Finland

In Finland, the winter months in particular are windy compared to the summer months. There are areas well suited to wind power production on the coast, in maritime areas, on the fells and in many places inland. In recent years, wind turbines have been built in greater numbers than in previous years.

Renewable and near-zero emission energy

Finland is committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions to combat climate change. Wind power is renewable energy and virtually emission-free. In addition, building wind power increases the share of domestically produced energy and reduces import dependency. The National Energy and Climate Strategy 2030 aims to increase the use of renewable energy to more than 50% of final energy consumption in the 2020s.

Building wind power will increase the share of domestically produced energy and reduce import dependency.

To achieve this goal, renewable electricity production was put out to tender in late 2018 under the new Production Subsidies Act. The Energy Agency organised a technology-neutral tender for 1.4 terawatt-hours of production. Bids could be submitted for wind, solar, biomass, biogas and wave electricity, but all projects in the competition were wind power, as it is the cheapest way to generate electricity. In recent years, more and more wind power has been built without state subsidies.

Increasing size of installations

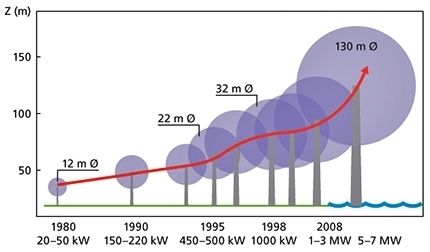

The average size of plants in Finland has increased significantly in the 2000s and is now over 4 megawatts (MW). The largest wind turbines in Finland are already 5.6 MW. As wind farms are built offshore in the future, the size of individual turbines will continue to increase.

The Development of Wind Power in Finland

At the end of 2023, Finland had a total of 1 601 operational wind turbines with a capacity of 6 949 MW.

In 2023, Finland’s wind farms will produce 14.4 TWh of electricity, which is equivalent to around 18% of Finland’s electricity consumption.

The wind sector has reached its production target of around 6% for 2020, even though the full wind power quota of the feed-in tariff was not reached. This target was achieved thanks to technological progress: new wind turbines produce more electricity than older generation turbines.

Typically, onshore wind farms have between 6 and 20 turbines, but the largest planned sites have up to 100 turbines. Planned onshore wind farms are located all over the country, but the larger concentration is around the coast of the Gulf of Bothnia. Higher tower heights also allow wind power to be built in forested inland areas, where good wind conditions are higher up the coast.

The most typical size of offshore wind turbines is around 3-7 megawatts. In total, the planned projects include around 380 power plants with a combined capacity of around 2 800 MW. The offshore wind farms are located relatively close to the coast (around 2-20 km) and vary in area.

The Finnish Renewable Energy Association’s website contains a summary of planned projects published in Finland. There is also a map showing the location of projects in different parts of Finland. More detailed information on more advanced projects can be found on the websites of the Centres for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment (ELY Centres) and project managers.

Elsewhere online:

Wind Power Technology

How does a wind farm work?

Wind is created when air moves as a result of temperature and pressure differences between air masses. The kinetic energy of the wind can be converted into rotational motion by the blades of a wind turbine. The blades rotate a shaft connected to a generator. In the generator, the rotational energy is converted into electricity, which is fed into a transformer and then into the grid.

Modern wind turbines are based on aircraft technology. Most of them are three-bladed, horizontal-axis turbines with rotors that turn in the tower according to the wind.

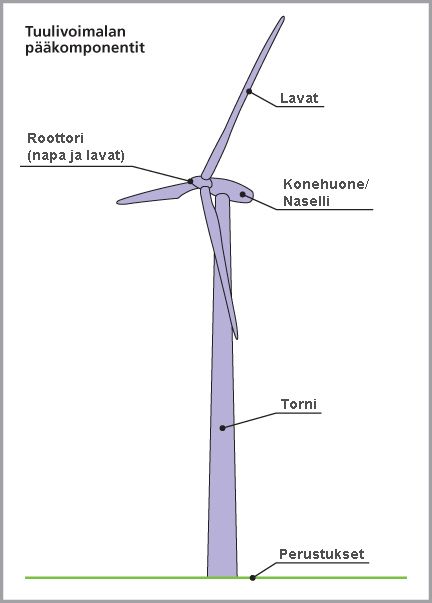

Power plant components

A wind turbine consists of a platform, an engine room (including the generator and gearbox), a transformer, a tower and foundations. The towers of industrial-scale power plants range in height from 50 metres to around 180 metres. The size of wind turbines has increased considerably in recent years, with turbines built in the 2010s having a pole height of 140-175 m. Rotor diameters range from 40-150 m. Towers are usually tubular steel towers attached to concrete or steel foundations.

The different power plant manufacturers’ models differ to some extent due to different technical solutions. The main external difference is usually the shape and size of the engine room, but there are also differences in the towers.

The capacity of wind turbines has increased significantly in recent years. While existing onshore wind turbines are typically in the 1-3 megawatt (MW) range, those currently under construction or planned are typically around 4-6 MW. The largest onshore wind farms on the market are around 8-10 MW and offshore wind farms are well over 10 MW.

A wind energy area or wind farm is an area with several interconnected power plants that are connected to the electricity grid as a whole. In these areas, the turbines are placed several hundred metres apart. The spacing is determined by a number of factors, such as the size of the turbine, the number of power plants and the layout of the plants. The distances between wind turbines should be about five times the diameter of the rotor, i.e. between 600 and 1 000 metres.

The wind turbine requires a wind speed of about 3 m/s to start up. The power output of the plant increases rapidly with increasing wind speed. The turbines reach their rated power, according to their characteristics, when the wind speed is around 10 to 15 metres per second. When the wind speed increases from 15 to 25 m/s, the power output may have to be limited. In general, the plant will shut down at wind speeds above 25-30 m/s to avoid damage to the plant.

The plants will be built to be automated, so the workforce will be needed mainly for fault repair and maintenance. The lifetime of a wind turbine is 20-30 years, during which time parts will need to be replaced and repaired.

Sources:

The power of wind brochure. Motiva Oy and OPET Finland in cooperation with the Finnish Wind Energy Association.

Placement of the Power Plant

The siting of wind farms is largely determined by technical and economic factors, as well as the environmental values and other land uses of the areas where they are located. The effects of environmental factors on the siting of installations are discussed in more detail in the section on the environmental and other impacts of wind power.

Many factors influence the technical and economic viability of an area. Good wind conditions alone are not enough to guarantee the project’s viability. The cost of building a power plant will increase significantly if it is not easily connected to existing infrastructure, such as the electricity distribution network and roads.

Wind conditions

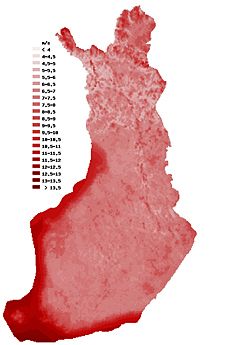

Wind conditions are the most important factor in choosing the most technically and economically viable location for wind turbines. In order to identify suitable areas with sufficient wind speed for wind power generation, the Wind Atlas project was carried out to model wind conditions in Finland on a national scale.

Since the Wind Act (2009), wind power projects have been planned and power plants built not only in coastal and fells areas, but also in inland windy areas.

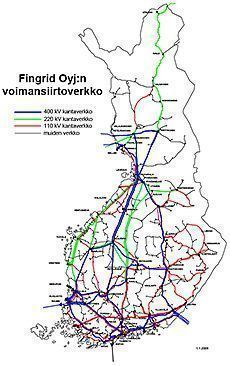

Connection to the electricity network

Connecting wind farms to the electricity transmission grid will affect the overall cost of the project, especially if the transmission lines are long. In addition, the connection may have a supra-municipal impact and require modifications to the substation or the construction of a new substation.

Typically, wind farms connected to the grid have a capacity of more than 15 MW. Connecting less than this to the grid is generally neither appropriate nor cost-effective. The project promoter must agree in good time with the grid operator on the technical feasibility of connecting the wind farm.

Fingrid, the Finnish transmission system operator, ensures that the transmission system has enough capacity to transport even large amounts of locally produced electricity to where it is consumed. The concentration of wind power, especially in Ostrobothnia and northern Finland, increases the need for increased transmission capacity, while electricity consumption is concentrated in southern Finland. Fingrid is therefore planning and building a large amount of new transmission capacity.

Infrastructure supporting construction and maintenance

The overall cost of the project is reduced if the infrastructure for construction and maintenance of the power plants is already largely in place.

The large and heavy components of wind turbines place their own demands on the roads used for transport. The roads must be stable and not have too steep hills to transport the turbine components to the construction site. Existing roads that meet the above requirements will reduce costs considerably. However, a wind power company will often upgrade existing roads before construction work starts.

The site will affect the foundations of the wind turbines and therefore the cost. It is usually easiest and cheapest to build on solid ground.

What if there is no wind?

Wind power production fluctuates momentarily, so wind power cannot be the only source of energy, but needs other electricity generation to balance the gap between consumption and production. Regardless of the generation mix, the electricity system must be prepared for unexpected outages. Calm days, which are rare in Finland, are not a problem when wind power is used to generate only part of the electricity.

When more wind power is built than the fluctuation range of electricity consumption, more regulating power is needed in the system. In Finland, the main sources of balancing power are hydropower and electricity purchased from neighbouring countries. The Nordic electricity market’s electricity exchange (NordPool) can balance short-term fluctuations in production and consumption. Technological developments are also increasingly enabling consumers (both large and small) to participate in balancing electricity through flexibility in their own consumption.

Support for Wind Power Construction

Although wind power is still partly subsidised by the state, wind power is still one of the most economical ways to increase renewable energy production in Finland. The newest power plants have also been built entirely without state support.

Feed-in tariff system for wind power

The support for the production of electricity from renewable energy sources came into force in March 2011. It pays a guaranteed price of €83.50 per megawatt-hour for wind power. If the market price of electricity is lower, the wind producer is paid the difference between the market price and the guaranteed price. If the electricity price is below €30/MWh, the subsidy becomes a premium of €53.50/MWh on top of the market price. The total guaranteed price is available for 12 years.

In spring 2015, the Finnish government decided to close the feed-in tariff scheme for wind power. The amendment to the Production Subsidy Act entered into force on 26 October 2015 and the feed-in tariff scheme was closed for new wind turbines on 1 November 2017. Since then, no new wind turbines have been accepted into the scheme.

However, the emission reduction targets are getting tighter and in late 2018, renewable electricity production was put out to tender under the new Production Subsidy Act.

7 projects received a positive grant decision. Each successful electricity producer will receive a pay-as-bid premium and the subsidy will be paid for 12 years. The subsidy period starts at the latest three years after the approval decision.

Offshore wind pilot project

In order to gain experience in building offshore wind power, the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment (TEM) selected the offshore wind farm planned by Suomen Hyötytuuli Oy in Tahkoluoto, Pori, as a pilot project for offshore wind power. The offshore wind pilot project aims to demonstrate wind turbine and foundation solutions suitable for the conditions in the Baltic Sea, which will enable large-scale offshore wind power construction in the icy conditions of the Baltic Sea in the future.

In 2014, TEM granted EUR 20 million in investment aid for the project. In addition, the project is eligible for production subsidies based on the amount of electricity produced for a period of 12 years. The aid was granted on condition that the beneficiary of the aid must provide information to other offshore wind project developers on the construction, operation and maintenance of offshore wind farms. In the case of the project selected, the testing of offshore platforms in ice conditions was considered significant.

Wind Power Construction Planning

The Land Use and Building Act (132/1999, MRL) sets the framework for wind power and other types of construction. In addition, an amendment to the wind energy law (134/2011, MRL) entered into force in 2011. The amendment allows for more frequent use of the master plan as a planning tool for wind energy development.

The general plan designates areas suitable for wind energy. Depending on its location and size, the wind power project itself will be implemented on the basis of detailed planning and/or licensing decisions.

In addition, the implementation of a wind turbine and power plant may require an environmental impact assessment procedure under the EIA Act (525/2017, EIA). If such an EIA is required, the plan may be extended to meet the requirements of the EIA Act.

The construction of a wind farm always requires either a building permit or an operating permit. In addition, any wind turbine over 50 metres in height needs to be approved by the Defence Forces.

Depending on its location, the wind farm may also require:

- an environmental permit under the Environmental Protection Act (527/2014, YSL),

- a permit under the Water Act (587/2011, VL) and/or

- an overflight permit under the Aviation Act (864/2014).

Elsewhere online:

5.2.1999/132 – Land Use and Building Act

134/2011 – Act amending the Land Use and Building Act

252/2017 – Act on Environmental Impact Assessment Procedure

Zoning

The Land Use and Building Act (132/1999, MRL) determines whether the construction of wind turbines requires the planning of the area or whether the turbines can be built solely on the basis of permit decisions.

According to the Land Use and Building Act, a plan should be based on sufficient studies and surveys. When drawing up a plan, the environmental, social, cultural and other impacts of the plan and the alternatives under consideration must be adequately assessed. The studies shall be carried out for the whole area on which the plan is likely to have a significant impact.

An open and interactive way of working

The Land Use and Building Act requires an open and interactive approach. The organisation of interaction and the assessment of the impact of a plan are key starting points in the planning process and are closely linked to each other. When drawing up a plan, a plan for participation and interaction procedures and for assessing the effects of the plan (participation and assessment plan) must be drawn up at a sufficiently early stage.

The impact assessment is planned and programmed in the work programme of the plan at the inception stage. The impact assessment and analysis provides planners, stakeholders and decision-makers with information on the impacts of the plan, their significance and the possibilities for mitigating adverse impacts. Nowadays, a plan can often be extended to meet the requirements of the EIA law, so that a separate EIA study is not required.

The amendment to the Land Use and Building Act concerning wind power construction entered into force on 1 April 2011. The amendment often allows building permits to be granted directly on the basis of a general plan.

National regional development objectives

According to the National Spatial Development Goals, regional planning must indicate the most suitable areas for wind energy not only in coastal, maritime and mountain areas, but also throughout the inland areas.

Wind turbines should preferably be located in a centralised manner in multi-turbine units. In addition to the specific objectives for wind power, other national regional development objectives must be taken into account in the planning of wind power areas.

In their activities, state authorities must take into account the national regional development objectives, promote their implementation and assess the impact of their measures on regional development and land use.

The planning of the province and other land use planning must take account of the national regional development objectives in such a way as to promote their realisation.

Regional plan

A regional plan is a general plan for the use of land in a region or part of a region. A regional plan can also be drawn up as a regional plan for a specific type or types of land use. A regional plan indicates national, provincial, regional and supra-municipal land use needs.

The boundaries of a wind power area designated in the regional plan may be specified in the general or town plan. The location of a wind power area designated in the regional plan may also be changed in a more detailed plan if there are justified reasons for doing so, for example, based on more detailed studies. However, a more detailed plan cannot be contrary to the regional plan. If no wind energy areas are designated in the regional plan, the suitability of the location for wind energy should in principle be determined by the general or town plan.

When drawing up a regional plan, the issues mentioned in the content requirements of the regional plan must be clarified and taken into account to the extent required by the regional plan’s function as a general plan. Among other things, the preservation of the landscape, natural values and cultural heritage impose restrictions and boundary conditions on wind energy development.

Master plan

A master plan is a general land use plan for a municipality. Its purpose is to provide general guidance on the location of different activities in a community and to coordinate these activities. A master plan may also be drawn up to guide construction and other land use in a specific area. The municipality decides whether to draw up a general plan and it is approved by the municipal council.

When drawing up the general plan, the steering effect of the regional plan must be taken into account. The land-use solutions adopted in the regional plan must be taken as a basis for the preparation of the master plan. When drawing up a general plan, the issues referred to in the content requirements of the general plan must be clarified and taken into account to the extent required by the guiding objective and the precision of the general plan to be drawn up.

Following a change in the law that came into force in 2011, wind power construction can be based directly on a general plan, the so-called wind power master plan (MRL 77 a §). When drawing up a wind power master plan, in addition to the other provisions of the master plan, it must be ensured that the master plan adequately guides construction and other land use in the area concerned, that the planned wind power construction and other land use is compatible with the landscape and environment, and that the technical maintenance and electricity transmission of the wind turbine can be organised (MRL § 77 b).

If a wind power master plan is drawn up mainly at the request of a private interest and on the initiative of the person undertaking the wind power project or the owner or holder of the land, the municipality may charge him or her for all or part of the costs incurred in drawing up the master plan (MRL 77 c §).

Site plan

The zoning plan regulates in detail the construction and other land use of the municipality. A land-use plan must be drawn up when the municipality’s development or land-use management needs require it (MRL 51 §). The municipality decides whether or not to proceed with the zoning of a particular area. A landowner may submit a proposal to the municipality to draw up a zoning plan, but the landowner does not have the right to obtain a zoning plan for his or her land.

If a land-use plan or change to a plan is mainly required by a private interest and has been drawn up on the initiative of a land owner or holder, the municipality has the right to charge him/her for the costs of drawing up and processing the plan (MRL § 59).

The solutions in the general plans are the basis for land-use planning. When drawing up a land-use plan, the steering effect of general plans must first be taken into account (MRL § 54). The land-use solutions adopted in the general plans must be taken as a basis for drawing up the land-use plan. The zoning plan for wind power must therefore pay particular attention to noise, safety, landscape, townscape and recreational issues.

In a zoning area, the suitability of a building site is determined in the zoning plan (MRL 116.1 §). As the granting of planning permission is directly based on the town and country plan, the plan must indicate the site for wind turbines and lay down provisions on the dimensions of wind turbines. However, the land-use plan may be drawn up in such a way that the locations of the wind turbine towers are not precisely defined. The land-use plan must also indicate the transport and electricity connections required for wind farms.

A plan or a planning reserve solution?

In principle, the suitability of the area for the siting of wind turbines should be determined by means of a plan. When drawing the line between a planning permission and a plan directly guiding wind energy construction, the more important criterion to be considered is the characteristics of the site and its surroundings, the size of the wind turbines and their relationship with the surrounding areas. A planning permission may be required for even one wind turbine.

If a wind project is located in a planning need area, it will require either planning or a planning permit, depending on its nature and location. A planning consent is applied to a development which, because of the significance of the environmental impact, requires a more extensive examination than the normal authorisation procedure.

A wind farm can be implemented by means of a planning permit if the use and environmental values of the site and its surroundings do not impose restrictions on the construction of wind power, and there is no significant need for coordination between wind power construction and other land uses. A planning parcel permit is not granted if the development is significant or will cause significant adverse environmental or other impacts.

Elsewhere online:

Stages of a Wind Power Project

The total time needed for a medium-sized wind power project (around 10 wind turbines) to go from initial studies to a completed wind farm is 4-6 years on average. Smaller projects can be completed in less than two years.

The progress of the project depends on a number of factors, including the timing of the studies to be carried out and the extent to which the local and regional authorities are familiar with the wind project.

The most common steps in a wind power project are as follows, some of which are carried out simultaneously:

- Preliminary survey and search for a suitable site.

- Negotiations with representatives of the municipality and the landowner of the site. Drawing up the lease agreements.

- Obtaining the opinion of the Defence Forces.

- Preliminary negotiations with the network operator.

- Starting wind measurements.

- A decision from the contact authority (ELY Centre) on whether to apply the environmental impact assessment (EIA) procedure and, if necessary, to start EIA studies.

- Zoning the area for wind power. The planning and EIA processes go hand in hand.

- Final negotiations with the network operator.

- How to apply for permits.

- Earthworks.

- Acquisition of power plants and start of construction.

For the general and local acceptance of a wind power project, it is important that the residents of the municipality and the area surrounding the planned wind power site are provided with sufficient information and opportunities to discuss the progress of the project.

Wind Atlas – Wind Data on a Map

The Wind Atlas is a computer modelling-based wind mapping tool. The Wind Atlas project resulted in an internet-based map interface that provides information on wind conditions in Finland. The map interface makes it possible to view site-specific wind conditions for the whole of Finland. The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment commissioned Motiva to coordinate the Wind Atlas project and the Wind Atlas was implemented by the Finnish Meteorological Institute and its subcontractors.

Detailed information on the map of Finland

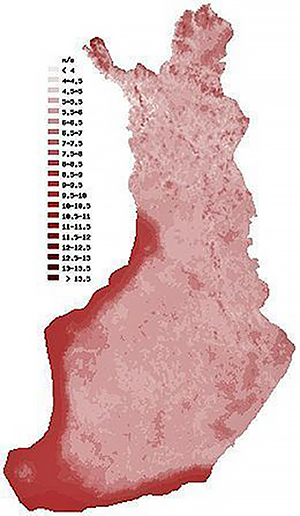

The purpose of the wind atlas is to provide as accurate a description as possible of wind conditions, such as wind speed, direction and turbulence, from 50 m up to 400 m in annual and monthly averages. The results are displayed in 2.5×2.5 square kilometre map boxes. For coastal and other windy areas, modelling has been carried out at an even higher resolution of 250 metres.

Photo. Distribution of mean wind speed (m/s) at 100 m at 2.5 x 2.5 square kilometres.

Result of millions of calculations

The creation of the wind atlas has required a large computer capacity, using a supercomputer at the Finnish Meteorological Institute. The new Wind Atlas is not the largest in terms of area, but it contains more comprehensive and accurate information than comparable wind atlases elsewhere in the world. Wind data from more than 1 million stations will be included in the new Atlas, many times more than the 50 stations in the old Atlas.

Wind Atlas has modelled a representative sample of wind conditions in Finland over the last 20 years. For the modelling, 72 months from 1989-2007 were selected and modelling runs were performed. The results are presented as annual and monthly averages calculated from the modelled wind data at three-hourly intervals.

Wind atlas an important tool

The Wind Atlas includes a dynamic map interface that allows you to view wind conditions in different parts of Finland. In addition, www.tuuliatlas.fi-sivusto was produced, which contains a wealth of information on wind characteristics and wind power.

The Wind Atlas is an important tool in Finland’s efforts to increase the use of renewable energy in line with national and EU targets. It is a very useful tool for wind energy developers and planners, among others. The reservation of areas suitable for wind power generation, for example in regional plans, has been limited by a lack of information on wind conditions in different parts of Finland, especially inland.

In October 2012, the Ministry and Motiva transferred the ownership of the Wind Atlas database and interface to the Finnish Meteorological Institute. The transfer is based on the Directive establishing the Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE). The Finnish Meteorological Institute, as the public authority, will maintain the Wind Atlas database and its electronic interface.

Freezing forecast linked to wind Atlas

In Finnish conditions, the blades of a wind turbine can freeze, which is called icing. Freezing occurs when the temperature of both the air and the wind turbine blade is below freezing and liquid water droplets are detectable in the air. On a cold surface, the droplets freeze. We have little freezing rain, or sub-freezing rain, but in winter the cloud droplets floating at low altitude quickly stick to cold surfaces.

Freezing can cause production losses and stress the structures of a wind turbine. Ice can also fly from the platforms, posing a safety risk. It is therefore advisable to equip the blades with a heating system.

The Finnish Meteorological Institute has produced an atlas of Finland’s ice cover and its data are included in the map interface of the Wind Atlas. The calculation of the glacier atlas is based on the same time series that were produced using numerical time series for the Finnish Wind Atlas.

The AROME model outputs include temperature, wind speed, cloud water content (cloud ice and cloud water) and different types of precipitation (rain, snow and sleet). These variables have been fed into a separate ice model, resulting in instantaneous ice accumulation rates and cumulative ice accumulation. In addition to the accumulation rates, an estimate of the production losses due to freezing has been calculated.

Elsewhere online:

Published on

Tuulivoiman yleisopas

Milja Aarni

Expert